I’ve started to see emotions the way I see software. They run in the background, they write instructions, and they update the system whether I approve or not. Even when I tell myself I’m “fine,” the amygdala — the tiny alarm tucked deep in the limbic system — is still firing signals that the hippocampus stores as meaning. This is why a single moment of embarrassment from ten years ago can still make my stomach tighten today. The body remembers even when the mind is busy pretending.

The mistake I made for years was believing that if a feeling calmed down, it disappeared. In reality, it just slipped beneath awareness. The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex suppressed the intensity, the way a parent shushes a child in a crowded room, but nothing was resolved. The feeling stayed alive in storage, waiting for the next similar moment so it could jump out with twice the force.

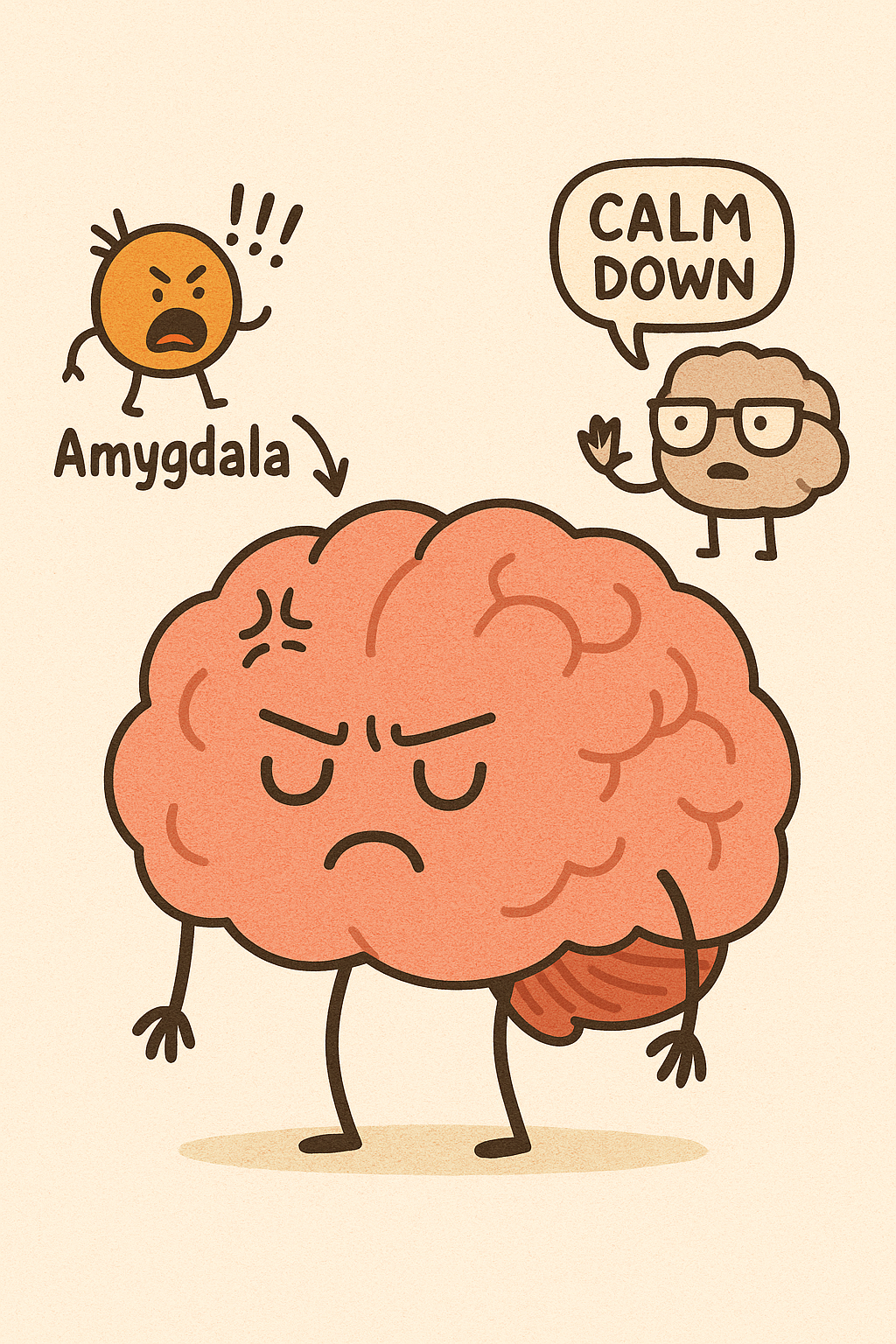

I didn’t recognize this pattern until much later. Back then, I thought I was being rational. I had a clean explanation for everything: “I’m tired,” “I’m overthinking,” “It’s not a big deal,” or the classic, “I don’t want to dwell.” Those responses feel mature because the prefrontal cortex speaks the language of reason. But the emotional circuitry speaks first. And when I ignore it, the limbic system keeps the emotional charge running in loops I don’t realize I’m following.

This is the part no one teaches: emotions aren’t fragile feelings floating around waiting for us to name them. They’re fast, ancient information-processing systems. They work like the built-in instincts of animals, except humans have layered so much story and culture over them that we’ve forgotten their purpose. The amygdala fires to protect, the hippocampus writes the lesson, the limbic system shapes motivation, and the prefrontal cortex interprets it all into something socially acceptable. If I skip that middle part — the actual feeling — the lesson my brain stores becomes distorted.

That distortion shows up everywhere. It decides who I trust, how close I allow people to get, how quickly I run, how long I cling, whether I hesitate or leap. It dictates the kind of love I think I deserve. It influences the risks I take and the opportunities I walk away from. And because I’ve always framed myself as pragmatic and self-aware, I used to blame everything on discipline, habit, and “not being consistent enough.”

But emotions have their own physics. I learned this the hard way. Let’s say I’m trying to move toward something new — a goal, a project, a relationship. As soon as I start, the amygdala lights up. Fear from old experiences gets activated. The hippocampus retrieves memories I thought were irrelevant. If I move toward courage, old hurt rises. If I move toward safety, loneliness and regret rise. Both sides trigger different archives, and suddenly it feels like I’m standing between two emotional landmines.

This is why follow-through collapses. It’s not inconsistency — it’s a tug-of-war between old emotional learnings programmed without my consent. Anyone of any age can understand this: a 15-year-old feels overwhelmed and pulls back; an 80-year-old remembers withdrawing from something decades ago without knowing why. Emotional memories don’t expire. They simply run quieter.

Talking about feelings doesn’t automatically process them. I learned this too. I could explain my anger without feeling it, narrate my sadness without touching it, intellectualize anxiety until it sounded like a TED talk. None of that changed what the emotional circuits were storing. Real processing feels different. The feeling is unmistakably present. My breath changes. My hands get warm. The amygdala fires, the limbic system responds, and instead of pushing it down, the prefrontal cortex stays open long enough for the emotion to complete its arc.

When that happens, the hippocampus updates the memory in a new way — without embedding fear or shame into it. That’s reprogramming. Not motivational quotes. Not willpower marathons. Not forcing myself to “think positive.”

There is a simple practice at the heart of this: when a feeling rises, I ask myself two things.

The first is what is this emotion trying to tell me? The second is what is this emotion trying to make me do?

These two questions open a tiny doorway. They put the prefrontal cortex in conversation with the amygdala instead of letting it silence the alarms. The emotion becomes information instead of a threat. The impulse becomes visible instead of automatic. Suddenly I can choose how to act instead of reacting from old code.

This is where everything starts to change. When I allow the feeling to be fully present instead of numbed, the system finally completes the loop. The emotion settles on its own, the charge softens, the limbic system stops pushing me toward old reflexes, and the hippocampus stores a cleaner version of the memory. The next time I face something similar, I don’t feel ambushed by my own nervous system.

People talk about emotional strength as if it’s about staying unshakable. I’ve started to see it differently. Strength is allowing the amygdala to fire without letting it drive. It’s giving the limbic system space to express what it remembers. It’s letting the hippocampus rewrite the meaning. It’s giving the prefrontal cortex the final say, not the first punch.

When that happens, the tug-of-war disappears. Follow-through becomes easier not because I became disciplined but because the internal coding stopped pulling me backward. Boundaries become cleaner not because I hardened but because guilt and fear stopped running the show. Relationships become steadier because I’m not dragging old emotional debris into new rooms.

The freedom is subtle, but unmistakable.

Numbing feels safer. Processing makes life lighter.

And the real work is not dramatic or grand. It’s simply choosing to feel long enough that the system updates itself, so instinct and intention finally stop fighting and begin moving in the same direction.

Leave a Reply