Jimmy Chin still remembers the sick feeling in his stomach.

Hanging from a fixed line thousands of feet above the Yosemite Valley floor, camera in hand, he wasn’t just a filmmaker that day—he was a witness to something that had never been done before. Below him, moving with the eerie precision of a tightrope walker who long ago made peace with the possibility of falling, Alex Honnold was free soloing El Capitan. No rope. No margin for error. No second chances.

“I remember thinking,” Chin recalls, “If he falls, it’s not just the worst day of my career—it’s the worst day of my life.”

Free soloing, by its nature, is a one-act performance. There is no rehearsal, no safety net. You send it, or you die. And El Capitan? That’s not just a climb. It’s the most iconic granite monolith on Earth, a 3,200-foot wall that has humbled the best climbers in history—most of whom wouldn’t dream of climbing it without ropes.

Yet on June 3, 2017, Honnold arrived at the base of El Capitan at dawn, chalked up his hands, and started moving upward. No fanfare. No announcements. Just another morning at work, except that one wrong move meant certain death.

The Impossible Feat That Climbers Wouldn’t Even Talk About

Among climbers, the idea of free soloing El Capitan wasn’t even discussed. It was too outlandish, too impossible. If you had suggested it at a campfire in Yosemite, people would have laughed. It was like someone saying they planned to run a marathon in under an hour. It wasn’t a matter of skill—it was a question of what the human body and mind were capable of enduring.

Even for elite climbers, the idea was absurd. “The margins are so small,” said Tommy Caldwell, the legendary big-wall climber and Honnold’s friend. “There’s no place for error. And every person who has made free soloing a major part of their life is dead.”

The difficulty wasn’t just physical; it was psychological. How do you stay calm when a single slip means death? Honnold’s approach was systematic. He treated El Capitan like a surgeon memorizing the incisions for an operation. He rehearsed every sequence, climbed the wall repeatedly with ropes, wrote down every movement. By the time he attempted the free solo, he had visualized every handhold so many times it felt inevitable.

There was one section, though, that remained terrifying: the Boulder Problem. One of the hardest parts of the climb, 2,000 feet up, required Honnold to press his thumb against a miserable hold and execute a karate kick to a distant foothold—an outrageous move, even with ropes. If he missed, it was over.

The Ethical Dilemma of Filming It

For Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi, directing Free Solo was a moral minefield. Chin, a climber himself, knew the risks. If they filmed it and something went wrong, would they be complicit? Would their presence push Honnold into doing something he wasn’t ready for?

Chin almost walked away from the project. The idea of filming a friend’s potential death was unbearable.

The team set a strict rule: Honnold should never feel their presence. If he looked up and saw a cameraman, it meant they had failed. The crew stationed themselves strategically, using remote cameras wherever possible. When Honnold arrived at the Boulder Problem, the film crew in the valley held their breath. If he hesitated, if he backed down, they wouldn’t push. It had to be his decision.

He didn’t hesitate. He executed the karate kick flawlessly and kept moving.

The Psychology of Alex Honnold

Honnold is wired differently. Scientists have literally studied his brain. An MRI scan showed that his amygdala—the part of the brain that processes fear—barely activates under normal circumstances. Where most people feel a gut-wrenching jolt of terror, Honnold feels… curiosity.

His childhood may explain some of it. His father was intensely quiet, his mother relentlessly demanding. Perfection was expected. Whether that shaped Honnold into a man who pursued perfection on a rock face is open to interpretation, but one thing is clear: he is singularly focused.

He memorized every move, trained relentlessly, and stripped his life of distractions. He even wore the exact same clothes he had trained in for months to eliminate any variables. His success wasn’t an act of reckless courage; it was an act of obsessive preparation.

The Moment of Triumph—and the Filmmakers’ Relief

When Honnold pulled over the final ledge, 3,200 feet above the valley floor, he didn’t pump his fists or scream in victory. He simply smiled, turned to the camera, and said, “I’m so delighted.”

For him, this was the logical conclusion of years of work. For the filmmakers, it was a moment of sheer relief. Chin, who had spent the morning with knots in his stomach, could finally breathe.

The Film That Changed Adventure Filmmaking

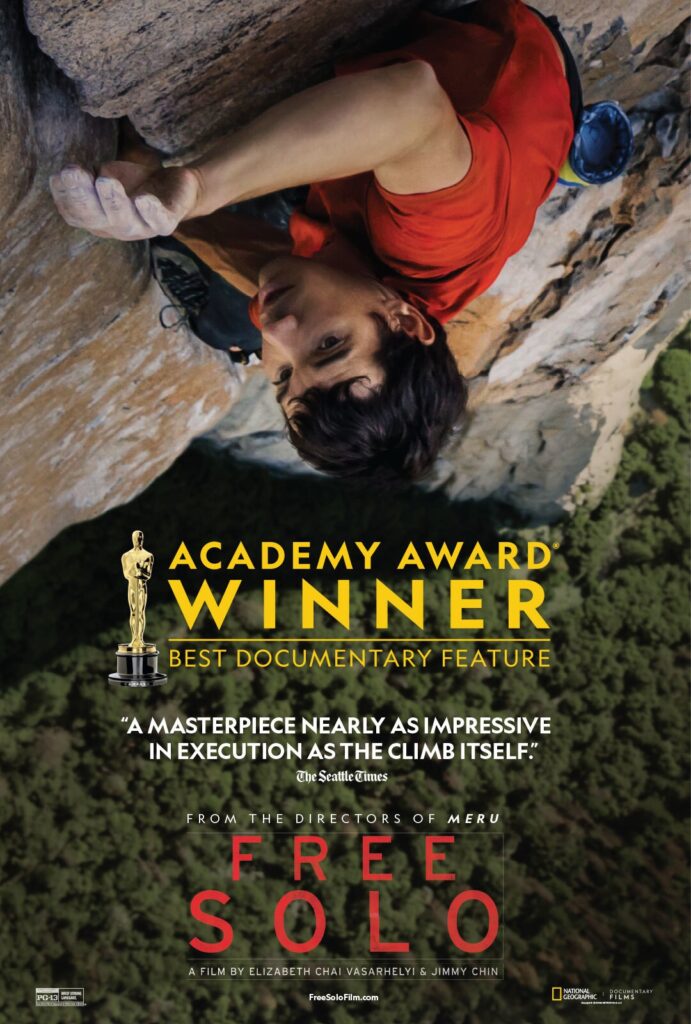

When Free Solo hit theaters, it left audiences shaken. People walked out with sweaty palms, their hands gripping the arms of their seats as if they had just been on the wall themselves. The film became a cultural phenomenon, breaking box office records for a documentary and winning the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Even non-climbers were drawn in. The film wasn’t just about climbing; it was about the pursuit of the impossible, the tension between ambition and safety, and the psychological makeup of a man who lives on the edge of life and death.

For Chin and Vasarhelyi, Free Solo was the result of years of trust, collaboration, and hard decisions. They fought over structure, debated how much of themselves to include in the film, and polished every detail. In the final stages of editing, they replaced outdated Google Earth images with better ones at the last minute—because when you’re telling a story about obsession and perfection, every detail matters.

The Legacy of Free Solo

Honnold’s climb remains one of the most audacious athletic achievements in history. Not just because of its difficulty, but because of what it reveals about human capability. How far can discipline, preparation, and sheer willpower take us?

For Honnold, the answer was 3,200 feet up a sheer rock face, alone, with nothing but his own skill to keep him alive.

For the rest of us, it’s a reminder: the limits we assume are often far from the limits that actually exist. What would it take to strip away every excuse, every distraction, every fear, and just go?

Alex answered that question for himself. The real question is: what’s our version of it?

Leave a Reply